The Tradition of Buddha’s Robe

A Dharma talk given by Sr. Candana Karuna

At IBMC 9-24-06

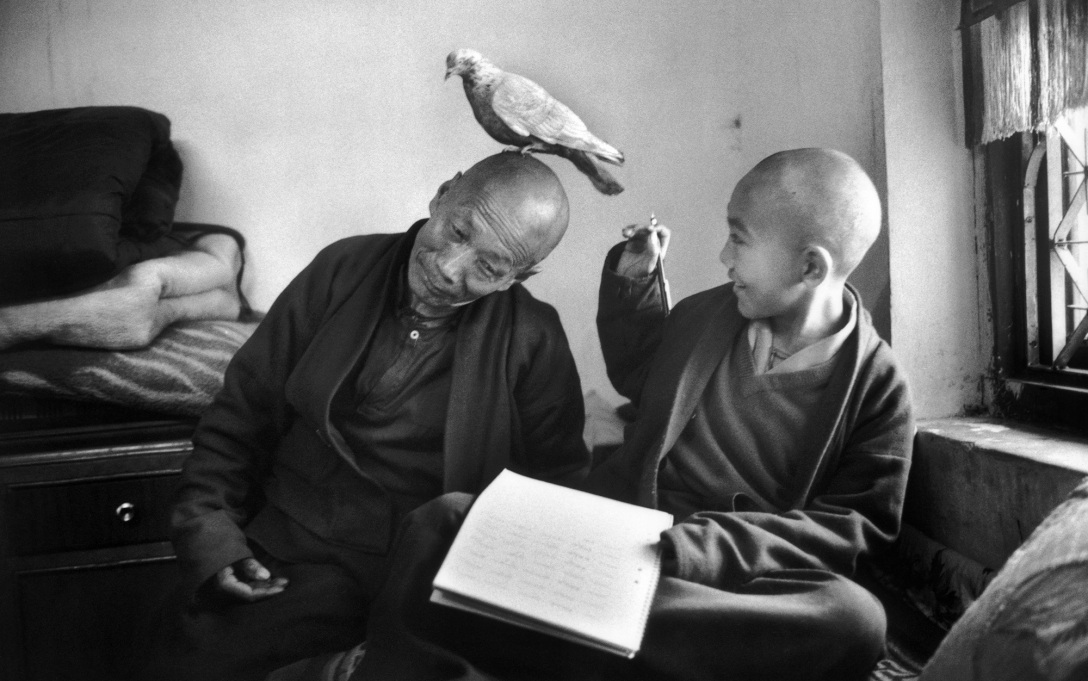

During the past year, I’ve noticed a lot of people wondering about Buddhist robes: why are there so many different colors and styles, why are they worn, what do they mean, what’s the big deal? It can be confusing. Doubly so here at IBMC, where there are not only many Buddhist traditions represented, but there are also differences in robes among those ordained within the American Vietnamese Zen tradition of our founder, Dr. Thich Thien-An.

Answering questions about Buddhist robes is easy on the surface, but each answer seems to lead to more questions. For some Buddhists, these answers are important; for others, even the question of robes is extraneous. Sometimes one explanation contradicts another or even seems to go against the spirit of Buddhism.

I like questions. I don’t have all or even most of the answers, and I still have questions, because in researching this subject I’ve discovered that for almost every statement I’m about to make, you can find a completely different answer. Sometimes, it’s simply that the different schools of Buddhism have different explanations or ways of doing things; at other times, language issues arise and translations are not reliable.

At any rate, this morning let me present you with what I have learned, my best guess, in trying to demystify the Tradition of Buddha’s Robe.

Siddhartha Gautama, the man who would become Buddha, was born a son of the Shakya clan and grew to manhood in an entitled and sheltered life during the 6th century BCE in India. Encounters with sickness, old age and death shattered his complacency and made him question the privileged experiences and assumptions of his life. He renounced home and family in order to devote himself to answering the questions of suffering and, as was the custom, traded his fine clothing away for that of a mendicant seeker.

So, what did beggar’s clothing look like? In most representations of the Buddha, such as the figure on our altar, his clothing looks pretty good: classic simplicity – clean lines and not a hole or stain in sight. Presumably, that’s because he’s usually shown after his enlightenment, when his robes were cared for by attendants and replenished by donations.

But even if you find a statue of the ascetic Siddhartha – hollowed cheeks, sunken eye sockets and ribs like desiccated bones – although he looks terrible, the loincloth looks neat and tidy. Take it with a grain of salt, because there are no contemporary portraits extant. In fact, it was hundreds of years after he passed into parinirvana before anyone thought to make an image of the Buddha. And art, by its nature, idealizes. So, don’t look to statues or artwork as a primary source – they simply tell you about the culture in which they were created.

But here’s what we are told in the sutras about mendicant robes during that time. They were made from discarded scraps of cloth, or what is called in Sanskrit pāmsūda or pāmsūla. There are various lists identifying what constitutes pāmsūda. For example, cloth that has been 1) burned by fire, 2) munched by oxen, 3) gnawed by mice, or 4) worn by the dead. The Japanese equivalent of pāmsūda is funzoe, a polite translation of which is “excrement sweeping cloth” and indicates another potential source.

These scraps were scavenged from the trash, out in the fields, by roadsides or even from the cremation grounds. Any truly unsalvageable parts were trimmed off and the resulting bits were washed and sewn, piecemeal and without pattern, into a rectangle large enough to wrap around and cover the mendicant. Then the rectangle was dyed, using gleaned roots and tubers, plants, bark, leaves, flowers or fruits, especially heartwood and leaves of the jackfruit tree, which resulted in a variable and generic color known in Sanskrit as kashaya, denoting mixed/variegated, neutral or earth tones. It’s also defined as “color that is not pure” or “bad color.” I have also been told that it refers to colors considered ugly, colors chosen to renounce that culture’s values. This also ties in with another connotation of the word kashaya, which is impurity or uncleanliness, reflecting back to the source of the cloth used.

We’ll return to color and style later, but this is the clothing Siddhartha Gautama wore as he studied with and surpassed several prominent teachers of that time, and undertook to master the most severe ascetic practices. Even then, he found them as ultimately empty of answers as was his early life. Finally, he turned away from those paths, sat down under the Bodhi tree with his questions and found the solution to suffering.

After his enlightenment, he began to teach and many of those who heard his teachings – mendicants, former teachers, householders, even his own family and royalty – left their pursuits and followed him forming the Sangha of monks and, later, nuns. Their clothing was not codified, and various sutras refer to a variety in dress, some of it fairly fantastic. Tradition has it that those who ordained with the Buddha, as well as the Buddha himself, primarily wore the mendicant clothing of that time, essentially the same worn in India today; they all wore some version of a simple, serviceable, Kashaya robe.

This caused a problem for a Buddhist king named Bimbasara, who wanted to pay homage to Buddhist monks but was having trouble picking them out of the crowd. One day, he complained and asked the Buddha to make a distinctive robe for his monks. They were walking by a rice field in Magadha at the time, and Buddha asked Ananda, his personal attendant, to design a robe based on the orderly, staggered pattern of rows of the rice padi fields.

This original Buddhist robe comprised three parts, layered depending on activity and weather, and was therefore known as the “triple robe” (tricivara in Sanskrit):

1. Uttarasanga is the normal clerical robe. It is a large rectangle, about 6 feet by 9 feet, worn wrapped around the torso and covering one or both shoulders. Although all three parts were made of kashaya fabric, this piece was the robe that came to represent Buddhism as it traveled to other countries, and it came to be called the Kashaya Robe. With its five-fold or five-column rice field pattern surrounded by a border, it is regarded as symbolic of a Buddhist’s relationship with the Buddha and his teachings

2. Antarasavaka is a lower robe, wrapped around the waist to knee like a sarong and tied at the waist with a flat cotton belt. According to the monastic rules or Vinaya, a monk could wear it by itself if he was on his own, sick, crossing a river or looking for a new Uttarasanga.

3. Sanghati is an extra robe, often made of two layers, which is used for extra warmth or may be used, spread out as a seat or bedding. It is sometimes folded and placed on one shoulder.

This “triple robe” traveled from India throughout the world as Buddhism spread and was adapted, as Buddhism has adapted, by each country and culture it encountered.

I’d like to go on a brief tangent and mention robe relics, those purported to be of an actual, worn-by-the-Buddha variety. A tradition of hand-me-down robes was extant during the Buddha’s lifetime; the sutras tell us when Ananda agreed to become the Buddha’s attendant, he stipulated that he would not take any of the Buddha’s robes because he didn’t want to create the appearance of favoritism. Since the Buddha taught for 45 years after his enlightenment, he undoubtedly went through quite a few robes, and there are quite a few stories of such robes or pieces thereof.

One of these relics was entrusted to the Buddhists of Sri Lanka by the Emperor Asoka in the 4th Century BCE but, unfortunately, the Buddha’s Robe relic disappeared or was destroyed during one of the many Chola invasions between the 9th and 13th Centuries CE.

Another story of such a robe comes from Zen Buddhism, which holds that the Buddha gave his robe to Mahakasyapa in testament to his deep understanding, evidenced when the Buddha held up a flower in silence and Mahakasyapa smiled, the only one to see the Buddha’s teaching. Some believe the 28th Indian Patriarch/1st Chinese Patriarch, Bodhidharma, brought this very robe to China and go so far as to say that it was passed to succeeding patriarchs until the Fifth Chinese Patriarch passed it to Hui-neng, with the instruction that there would be no more passing of the robe. Not every Zen Buddhist believes this in a literal sense; I personally suspect the Buddha’s Robe, at least in this case, was more symbolic of Mind-seal transmission than involving any actual original garment.

Back to the “triple robe,” which arrived in China with Buddhism well ahead of Bodhidharma, although it wasn’t Chan (which became Zen), and once it left India, the form of the “triple robe” as well as the terminology began to change. The Sanskrit word kashaya was transliterated into Chinese as jiasha in Mandarin, kasa in Cantonese, and came to be applied specifically to the Uttarasanga, or normal clerical robe.

While India’s climate is temperate, and the three rectangular robes provided sufficient warmth and protection from the elements, even a double-layered Sanghati didn’t cut it in China. So the Chinese layered additional, Taoist-style robes and jackets, or what we would recognize as kimono (although that’s a Japanese term), under the kasa. These garments had sleeves of various types, from relatively close-fitting to what we Americans think of as the archetypical Asian sleeve, the pendulous dogleg that may or may not be closed at the wrist.

China did not have a mendicant tradition, wherein monastics would be supported by the populace (nor was it likely official support would be forthcoming from a government steeped in Confucianism and Taoism). In order to be as self-sufficient as possible, Chinese monastics farmed and performed manual labor in addition to religious practice. Because the wrapped “triple robe” is not designed or conducive to this type of heavy work (especially when it’s freezing), the monks developed wrapped leggings, split skirts (like culottes) or pants as alternate forms of the lower robe or Antarasavaka.

The kasa, itself, also went through some changes. The original Uttarasanga had five columns in the rice field pattern and was large enough to simply wrap around the body and shoulders. Once Buddhism had left India, four small squares inside the outside corners and two larger reinforcing squares near the top border on either side of the center column were added to the kasa, modifying the original design. Ties and straps, or fasteners were attached, often in the form of a ring and spoke.

At some point, perhaps in China, Korea or Japan, a smaller version was developed, like the one I’m wearing which we call the rakusu. It has the five columns and is worn around the neck like a bib. The origin of the rakusu is one of the confusing questions for me. Some say that it developed during the transition to manual labor in China, because a full kasa was cumbersome. Some say it was originated during a time of persecution, so that Buddhists could wear the kasa, hidden and safe, under their outer clothing. It’s also been suggested that started as simply the “cloth bag that wandering monks wore to carry alms bowl and other small items,” which was later “formalized as a monastic ‘accoutrement’.” There are even Japanese scholars who believe that it was developed in Japan during the Edo or Tokugawa Era, as the result of sumptuary regulations which limited the size and fabric type of clerical wear (I suspect a bit of nationalism, here).

The other big change to the full-sized kasa was the addition of columns as the monastic advanced in ordination and power, whether spiritual or temporal. The basic five-fold robe expanded to accommodate a system of rank modeled after the traditional nine-grade hierarchical Chinese law, so that five grew to seven, to nine, to 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23 and 25 strips of cloth, often of rich or rare fabrics, providing a physical proof of one’s status.

Buddhism spread from China to Korea, and the Koreans adopted the term Kasa. They also maintain the rakusu or small kasa tradition, but did add a shortened kimono-type robe to be worn under the kasa.

Korean Buddhists introduced Buddhism to Japan, although eventually it was Chinese influence that overwhelmed and was wholeheartedly embraced by Japanese Buddhists: Taoist-style robes with wide arms, purple kasa, multiple columns, work clothes and all. The Japanese transliterated the Korean/Chinese kasa to kesa, or okesa, which is simply a polite Japanese format. The Japanese adopted the distinctive and practical work clothes, which they called samue, as the everyday working uniform of the monastic. They also created a new form of kesa, by developing a black wide-sleeved kimono-style monk’s robe which conforms to the spirit, if not the form, of the Kashaya Robe in that it is made from the pieces of cheapest fabric, which are sewn and dyed by the monk.

Japanese Buddhist monastics created many different robes, sacred as well as ordinary clothing, and it seems like they have 20 words for each one. As an example, I will simply mention the rakusu. In addition to the one we’re familiar with at at this temple, there is the Okau, a larger rakusu worn on the left shoulder (I believe that’s the style that looks a little like you’re wearing a barrel by one suspender), the Hangesa or “half kesa” given to lay people and the Wagesa or “small kesa” also worn by lay people who have taken precepts.

Japanese rakusu have sewn designs on the straps, or on the collar covering, where they fall across the back of the neck to indicate denominational sects: Soto is a pine, Rinzai is a mountain-shaped triangle, and Obaku is a six-pointed star. In addition, Rinzai and Soto traditions sew a large flat ring on the left strap. This ring is not functional, but recalls the shoulder fasteners of the full-length kesa. As a result of a reform movement known as the fukudenkai in the mid-20th century, some Soto Zen groups have eliminated the rakusu ring.

Buddhism entered Vietnam from India and later from China, although the Chinese forms became dominant. The Vietnamese prefer a close-fitting sleeve on the kimono, again illustrating that robe style often begins with an adaptation of a culture’s normal clothing and becomes institutionalized. A similar situation applies to the Vietnamese pajama-like work clothes: a monastic uniform, but not sacred clothing.

Within the Tibetan or Vajrayana tradition, the culture once again adapted the “triple robe.” Ordained male and female clerics wear a sleeveless tunic and lower robe or skirt. The Tibetan Kashaya Robe is variously called shamtab (five strips), chogu, or namba (25 strip, for high ordination).

American robes, such as they are to date, are largely determined by a teacher’s tradition. Variations occur due to personal preference, convictions, understanding, or simply opportunity. And sometimes, speaking for myself, it’s all about comfort.

Although the essential Buddhist robe was the Kashaya Robe, there have been variations in quality of material ever since the Buddha’s time. In the Pali tradition, six kinds of cloth are allowed for making the upper and outer robes of the “triple robe”: plant fibers, cotton, silk, animal hair (not human), hemp, and a mixture of some or all of them. There are other lists of materials, but it’s clear that a variety of fabrics were used throughout. Some were sumptuous. Some were simple or easy-care. Certainly, most of Asia seems to be using man-made fabrics right now. In the ultimate sense, of course, any material could be used, provided there is no attachment.

With reference to attachment, one interesting thing that is prohibited in the Vinaya is “sewing cowries shells or owls’ wings” onto robes. Evidently, some of the Buddha’s monks were adorning their robes and had to be restricted in their artistic or preening tendencies. When the Chinese embroidered scenes in gold thread in their ceremonial kesa, or the Japanese took a single elaborate weaving and simulated the pieced, rice field pattern by appliqueing brocade dividing strips, perhaps sewn to one edge only so that the loosely attached strips swayed like tatters — do you suppose that they were truly not attached? Not that I’m not appreciative of the craft and beauty of these kesa. I’m just wondering.

This finally brings me to color, back to the concept of kashaya – broken or variegated color – which probably was in a spectrum from yellow to a reddish brown from being washed and dyed with plant materials, sometimes saffron or tumeric. Because the materials and dyestuffs vary, colors are not consistent. They also fade and become soiled. According to Seung Sahn Sunim, the Korean Zen master, during the Buddha’s time, the monks wore yellow robes, because that was the color of the dirt and didn’t show soil when the wind was blowing.

In modern times, monastics of the Theravadan tradition in Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Thailand or Laos usually continue this tradition of saffron or ochre robes. One source I encountered claimed that forest monks wear ochre while city monks wear saffron, but concluded that this is not always the case.

Monastics in the Mahayana tradition wear many different colors, according to region, country, sect and ordination level. When Buddhism came to China, color changed and changed again; different temples in various regions wore different colors: yellow, light golden brown, brown, grey or blue, shades of black: pitch black, grey black. During the Tang Dynasty, the emperor awarded purple robes and honorary titles to high-level monks.

Japanese monastics usually wear grey or black. They adopted the purple kesa tradition, which was revoked in the 17th Century under the Tokugawa Shogunate. The emperor abdicated in protest and monks who resisted, no matter how high, were exiled.

Koreans wear grey, brown or blue robes.

In the Vietnamese Zen tradition the kimono robes are brown or yellow, or somewhere in between, and the kesa are yellow to orange. At IBMC, after 10 years at high ordination, the cleric may wear a red kesa.

The colorful robes of the Vajrayana tradition of Tibet range from the simple to some of the most elaborate in the world, from bright yellow to orange to maroon to a purplish-red according to School and Dharma level. Their versions of the Kashaya Robe are usually yellow. If their sleeveless tunic is trimmed with yellow brocade or they are wearing yellow silk and satin as normal attire, they are probably eminent monks or considered living Buddhas.

Americans tend to follow the color coding associated with their teacher’s tradition, although we do have a tendency toward individualism and downright contrariness when it comes to formalization. Our Rev. Kusala once suggested that American Buddhist robes might be blue denim.

As an example of how schools assign colors according to Dharma level, here’s what I think I know about IBMC’s Americanized Vietnamese Zen. Monks and priests wear some shade of brown robes with yellow/orange kesas. Fully ordained priests may additionally wear yellow collars or yellow piping around the collar. Laypeople, whether taking Refuge or atangasilas (eight-precept ordainees such as myself, Nam, Doug and Gary) wear the rakusu and, while not entitled to wear the larger kesa, we do get to wear these spiffy grey non-sacred robes.

One Soto Zen website mentions that Bodhisattvas wear black or dark brown kesas, so I guess IBMC and a large part of Japan are pretty far advanced.

With respect to bib-like rakusu, colors may reflect those of the kesa. At IBMC, ours are gold. In Korea, the half-kasa is brown. Or they may be a different, contrasting color to the kasa. In China, Chan-style rakusu are white. The Japanese wear blue, brown or black, with their rakusu first given during Refuge. No matter what color faces out, the Japanese back them with white cloth, on one side of which teacher writes the “Verse of the Kesa” while on the other, he writes his name, the student’s dharma name and the date of the Refuge ceremony. In Soto Zen, blue is for laypeople, black is for priests, and brown is the highest, for people who have received Dharma transmission from a lineage teacher.

However, not all Soto temples, even in Japan, follow the Dharma level color coding. One might receive a brown rakusu at lay ordination at one temple, but be chided at another temple for wearing a color reserved for someone at a much higher level. This actually happened to someone at two American Zendos.

Confusing? Yes, and that’s simply mundane style and color. Here’s a quick rundown of the symbolism of the Buddha’s Robe.

Kesa or Kashaya Robes, whether small and large, today are almost entirely “Symbol.” They are the Buddhist’s connection with the Tathagata. In Buddhist numerology, five is the number of the Buddha, which is echoed by the five-folds and five points of the rectangle: east, west, north, south, and middle. The Kashaya Robe is the robe of the renunciant, wherein the discards of the world are made pure and precious, yet the rice field pattern also represents and encompasses the world, in all the fecundity of agriculture. It can also be regarded as a mandala, geometric patterns of squares and lines which represent the universe and serve as a meditation object on many levels. The little squares on each corner represent the four directions or, perhaps, each of the Buddhist Dharma protectors. The center column is sometimes said to represent the Buddha, and the two flanking squares his attendants.

“The kesa is the heart of Zen, the marrow of its bones,” said Eihei Dogen, (1200-53 CE) who established the Soto branch of the Zen in Japan. It is the physical doctrinal symbol, the essence of Transmission, and essential to a sense of legitimacy. Dogen studied in China and received the kesa of a Chinese Zen patriarch who had lived a century earlier.

Dogen was somewhat fanatical on the subject of kesa, proselytizing its profound virtues, lamenting the decadent period wherein it provided the only lifeline and yet was so neglected. I recommend his Kesa Kudoku (The Merit of the Buddha Robe), Chapter 3 of his great work the Shobogenzo, which waxes poetic on the subject, while providing practical information concerning the making, care and use of the garment. I can provide copies by email if you are interested.

He wrote, “… one verse of the ‘Robe Gatha,’ [also known as the Verse of the Kesa]… will become the seed of eternal light, which will finally lead us to the supreme Bodhi-wisdom.” The Robe Gatha is a Zen chant which is said before one puts on the Kesa or Rakusu.

Here is one translation:

How great the robe of liberation

A formless field of merit.

Wrapping ourselves in Buddha’s teaching,

We save all beings.

Pretty marvelous, isn’t it? However, a cautionary story about the robes, appearances and reality comes to us from the founder of Rinzai Zen, Master Lin-chi I-hsuan, who lived in the 9th century CE, who said,

“… I put on various different robes…The student concentrates on the robe I’m wearing, noting whether it is blue, yellow, red, or white. Don’t get so taken up with the robe! The robe can’t move of itself; the person is the one who can put on the robe. There is a clean pure robe, there is a no birth robe, a bodhi robe, a nirvana robe, a patriarch robe, a Buddha robe. Fellow believers, these sounds, names, words, phrases are all nothing but changes of robe … Because of mental processes thoughts are formed, but all of these are just robes. If you take the robe that a person is wearing to be the person’s true identity, then though endless kalpas may pass, you will become proficient in robes only and will remain forever circling round in the threefold world, transmigrating in the realm of birth and death.”

Perhaps it is not a good thing to become too impressed or too attached, even to the kesa, although Master Dogen might disagree. Some American Buddhists chafe against robes as representative of the hierarchy of Asian Buddhism; they wonder if robes have any value. Some wonder if different robes encourage comparisons such as, “who is most enlightened?” or “who is the senior here?” Some believe robes intimidate newcomers or encourage pride as one advances. And some just don’t like the inherent formalism or the implied elitism. Many Americans, simply wear their robes or just a rakusu over ordinary clothes. Rev. S’unya often replaces his pajamas with Heartland Zen brown overalls. Perhaps we *are* developing American Buddhist robes. But then again, perhaps not: the Sangha at Spirit Rock in Northern California has decided not to wear robes or differentiating insignia at all.

As a final point and to thank you all for listening to me, I would like to address one additional aspect of the Tradition of Buddha’s Robe. Although I’ve run through the quick guide as to who wears what, when and why, I’d also like to leave you with a proactively positive way of approaching life with the help of the Buddha’s Robe.

In the Lotus Sutra, the great, some say the greatest, Mahayana Sutra, we encounter a specific concept of “putting on the Buddha’s Robe.” This appears in Chapter 10, “Teacher of the Law,” which addresses how to communicate with others, specifically when discussing Dharma. But I believe it is applicable to our everyday lives, whether chatting about the weather or politics or sitting, alone, with ourselves.

In this chapter, Shakyamuni Buddha explains “the three rules of teaching,” one of which is that a teacher must, “put on the Thus Come One’s robe,” before trying to teach the Lotus Sutra.

In the Sutra, Buddha is speaking metaphorically; he explains that his Robe is “a mind that is gentle and forebearing.” What does this mean? Gentle seems easy enough. Forebearing, or perseverance, seems to me to be the echo of Zen’s Great Effort, this time applied to communication. If we, as a people, were able to combine kindness with willingness to stay engaged in dialogue, even when disagreement, criticism or misunderstanding arise, a great many problems might simply be talked away. Unkindness breeds; if someone does not understand or rejects our position, we are tempted to return the favor. Rejection leads to anger or disengagement, our cliché of fingers-in-ears “La,la,la, I can’t hear you,” often resulting in frustration and sorrow. We lose the opportunity to communicate.

I believe that “gentle forebearance” comes from a resolve to develop one’s center – it nurtures seeds of equanimity. This requires inner strength, but also an open mind. Such a tremendous amount of effort is involved in simply acting, rather than reacting, in not becoming too attached to what you believe, to being right – because if you personalize dogma, it becomes a fixed barrier to dialogue, any attempt at discussion swirls around it and crashes.

This is not to say that one should be passively meek and it’s not a quid pro quo kind of situation. “I’ll be nice if you’ll be nice,” is not the goal here, although it is a nice side effect of being respectful. In fact, I think we should approach communication without expectation of reaching agreement or even understanding.

I may believe that, but I rarely achieve it. However, I offer this Dharma talk to you all in that spirit! May you all be warmly wrapped in Buddha’s Robe, open to dialogue but firm in your resolve and effort, and not perturbed by the questions of Buddhist couture.

Link: https://wisdomtea.org/2023/05/18/the-tradition-of-buddhas-robe/